Christian Theology, Affirmative Action, and Reframing a different Human Future (Part 1)

In light of the recent reversal of Affirmative Action by the US Supreme Court, I have been thinking about the role of Christian theology to assist us to move forward post-racially as a nation and a people. As a Christian theologian, I must first confess that theology is fundamentally a human invention, and theological doctrines are the product of human imagination and coordination. By articulating this perspective, I am also affirming the epistemological limits of the discipline of theology itself, and the many ways it may not contribute fully to improve social relations, political arrangements, and human dynamics in society. Secondly, I am also attesting to the intellectual constraints of theology to break certain barriers in society, including economic, political, cultural, gender, educational, or ethnic. In other words, I do not believe theology or theological thinking is adequate or has all the resources to help us solve all the mysteries and complexities in contemporary societies—especially those in the polarized contemporary American society. However, I believe that we should investigate the theological resources that are available to us to assist us in imagining and conceptualizing the possibility of a post-racial society and in reframing a different human future?

By stating that theology has both epistemological and intellectual limits, I am simply pointing out that every theological system or tradition (Liberal theology, Liberation theology, Feminist theology, Openness theology, Constructive theology, Black theology, Reformed theology) is grounded in a specific cultural tradition and geography that shapes its language, contents, and ways of expression. If geography and culture support the numerous ways we think and live theologically in the world and in communion with others, our theological tradition also reflects our respective culture and geography; thus, the temptation to rise above our own theological tradition to engage transculturally and globally calls for both intellectual modesty and theological humility.

Most Christian theologians believe that there is a revelatory aspect to Christian theology. The idea that God has voluntarily revealed his nature and perfect attributes, both communicable and incommunicable, transcendent and immanent, in the sacred pages of Scripture testify to this position. The belief that the Scriptures also have a revelatory character of the Divine provides the resource to think theologically both about the Scripture and God himself. A third proposition most Christian theologians embrace is that the moral qualities of God point us to the moral life we should aim for in this world, and that divine perfections are adequate to help humans create government, the arrangements of society and culture, the institution of laws, and the distribution of justice and equity in society. Finally, most Christian theologians maintain that the way of Jesus is a model for human living and relations, and that in the character of Jesus humanity finds the best available resources to foster the deeply-formed life in a tragically-fractured world.

Yet we must bear in mind everything that I said above about the virtues and merits of Christian theology is a form of hermeneutical exercise, but it is a form of intellectual gymnastics that has some consensual value among theologians, universally and globally. The theological vision of the Bible includes certain emancipatory concepts and ideas promising us there’s another way to live together in this world and correspondingly, there’s another way to (re-)organize human societies. The revelatory nature of Biblical theology provides a good orientation to explore the possibility to live, think, act, and govern post-racially in our contemporary moments.

Given that we already affirmed the revelatory character of both Biblical theology and Theological anthropology, we have adequate resources available to point us to the right direction, that is, to think anew and reimagine creatively a present and future that are not based on racial identities and categories in modernity. If the revelation of God provides enlightenment to the dark world and if divine revelation is the antithesis to anything that defers human flourishing and life together, then Biblical theology is an empowering enterprise we can lean on to progress toward personal growth and the collective realization of God’s original intent for human societies and governments.

I would like to close the first part of this conversation with this question: Could Christian theology provide us with a different language to undo the race concept and get rid of racial categories in society that are often deployed to describe certain human relationships, demonize certain populations, grant privileges and advantages to certain groups, and delay the common good in society?

Year: 2023

My Interview with John Morehand on Vodou and Christianity in Interreligious Dialogue

Last week, I had an opportunity to have a conversation with John Morehead, the host of Multifaith Matters, about interreligious dialogue between Vodou and Christianity. It was fun!

phttp://johnwmorehead.podbean.com/e/celucien-joseph-on-christianity-and-vodou-in-dialogue-in-haiti/

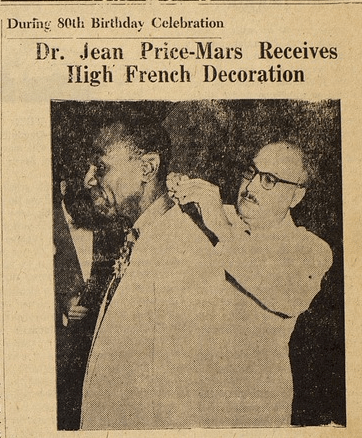

“Price-Mars: A Lesson on Perseverance and Commitment”

“Price-Mars: A Lesson on Perseverance and Commitment”

Here’s a lesson about commitment, perseverance, and dedication that I want to share with you from the life of Jean Price-Mars.

At 19 years old, Jean Price-Mars began his medical training at the National School of Medicine, Haiti’s only medical school at that time, located in the capital city of Port-au-Prince. In 1899, he received a government scholarship to finish his medical studies at “La Sorbonne”/University of Paris, in Paris, France. Due to financial difficulty, his studies were interrupted in 1901. Hence, he was forced to return to Haiti before getting his medical degree.

Twenty-two years later (I say 22 years later!), Price-Mars resumed his medical school in 1922 at the School of Medicine affiliated with Université d’État d’Haiti/the State University of Haiti. In 1923, he was awarded with his medical degree (M.D.) at 47 years old. Yes, he was 47 years old when he became a physician!

Immediately, he joined a medical team/clinic in Port-au-Prince to provide medical care to and cure the illnesses of the Haitian people. Because of his commitment to the Haitian peasants, the marginalized group in Haiti, he spent a lot of time riding his horse in the mountains and hills of Kenskoff to treat their diseases and make their life better. It was during his visits in Haiti’s countryside while spending time with the rural people that he began to do ethnological studies and attended more than 100 Vodou ceremonies. Jean Price-Mars would become the Father of Haitian ethnology and train thousands of students in the discipline.

His son, Louis Mars, following the footsteps of his famous father, also became a medical doctor. In fact, Dr. Louis Mars became the first Haitian psychiatrist. Like his father, he has written prolifically on the relationship between Vodou, psychiatry, and spirit possession. It should be noted that it was his father who inspired him to study psychiatric medicine, and he devoted his entire life caring for the Haitian people.

“Some Updates about My Intellectual Biography on Jean Price-Mars”

“Some Updates about My Intellectual Biography on Jean Price-Mars”

I published my first academic essay on Jean Price-Mars eleven years ago, the same year I graduated with my PhD from the University of Texas at Dallas (#UTDallas). The title of the essay is “The Religious Philosophy of Jean Price-Mars.” Journal of Black Studies 43.6 (2012): 620–645. Little that I knew back then that I would be devoting the next eleven years of my life working on an intellectual biography on the man.

I was introduced to Price-Mars in a course on “The African Diaspora” while I was working on my master’s degree at the University of Louisville (KY). The brilliant African-American professor, activist, and educator Dr. J. Blaine Hudson (1949 – 2013), who also served as the Chair for the Department of Pan-African Studies and the Dean of Arts and Sciences at the UofL introduced me to some of the most influential intellectual giants and activists in Black Studies and the African Diaspora, including W.E. B. Du Bois, Jean Price-Mars, Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, Aime Cesaire, Marcus Garvey, Amy Jacques Garvey, Francis Kwame Nkrumah, Stokely Carmichael, Amílcar Cabral, etc. That happened 20 years ago.

Interestingly, this class with Dr. Hudson has prompted me to pursue deeper knowledge and understanding about the histories, stories, experiences, and struggles of the people of African descent in the African diaspora, with a special attention on Black America and Haiti.

When I originally applied for the admission to the PhD program at the University of Texas at Dallas, I was accepted to the doctoral program in (Intellectual) History. At first, I wanted to do European history, especially contemporary European thought/history of ideas as academic research. I spent a whole year in the PhD program in History and took courses in the discipline. After my first year, I decided to change my major to (English) Literary Studies with an emphasis in three academic areas of research: African American Intellectual History, African American Literature, and Caribbean Literature and Culture. It was through my academic interest in African American Intellectual History that I encountered Jean Price-Mars for a second time. It was another life-changing experience for me. In addition to W.E. B. Du Bois, Price-Mars suddenly became my intellectual idol and dead mentor/teacher.

According to some people, if you have a keen interest in African American Studies and want to get a good handle of its intellectual enterprise, you just have to read everything W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) has written on the Black experience in American history. In the same line of thought, it is impossible to have a good grasp of Haitian history and its intellectual side without reading and understanding Price-Mars. Jean Price-Mars is the very embodiment of Haitian intellectual thought, both present and past, and reading Price-Mars is learning about Haiti and the Haitian people in all their complexity, dimensions, and challenges. Contemporary Haitian intellectual history is a footnote to the writings and ideas of Jean Price-Mars (1876 – 1969).

The current manuscript (the intellectual biography) is 479 pages + a 20-page bibliographic reference. Today, I finalized this exceptionally long and detailed bibliography (Chicago Style). It has been quite a tedious task, to say the least. As I am writing this note to you, I am thinking whether I should add a few appendices (maybe 3) that will offer an outline of Price-Mars’ life and writings–as I have done in my book on Jacques Roumain. What do you think? Would you find the appendices on the subject matter helpful in a book that is already long?

My conversation with Patrick Jean-Baptiste on Jean Price-Mars: Part 1

My conversation with Patrick Jean-Baptiste on Jean Price-Mars: Part 1

Christianity and Slavery in the United and Saint-Domingue (“Haiti”) Revised!

Christianity and Slavery in the United States and Saint-Domingue (“Haiti”) Revisited!

Contrary to the traditional belief and standard scholarship, it is not historically true that Christianity was forced upon the entire enslaved population in the United States and in the Caribbean, especially in Saint-Domingue (“Haiti”). Many of the slaves voluntarily embraced Christianity not as a new faith, but as a continuity of the African Christianity that had existed on the African Continent even before the transatlantic slave trade and the mass African immigration to the Americas.

The process of religious syncretism between Christianity—both Protestant and Catholic expressions—and West African religion, for example, was not a difficult process for many of the slaves because of their familiarity with African Christianity. In fact, various recent studies have shown the irrefutable evidence of the rich religious diversity of the Africans who had been dragged to the United States and Saint-Domingue. They were pious muslins, animists (practitioners of African traditional religion, such as African Vodoun or Dahomean religions), and Christians. It was not in the so-called New World that the Africans encountered Christianity—both Protestant and Catholic forms—for the first time. Both Christianity and Islam were already syncretized on the African soil through the lens of African animism before European colonization and transatlantic slave trade.

On the other hand, it should be acknowledged that colonial Christianity and colonial Christian catechism were used as tools to support slavery, pacify the enslaved population, maintain white supremacy, and keep the enslaved population under direct submission. In fact, colonial Christianity was one of the most powerful engines that helped to maintain the institution of slavery both in the United States and the Caribbean and Latin American regions. Paradoxically, biblical Christian teaching on the shared humanity of all people, both the master and the slave, both the colonized and the colonizer, as well as the undisputable equality and dignity of all people, was the most strategic rhetoric employed both by abolitionists (moralists and Christian abolitionists) and abolitionist movements to end slavery in the slave-holding societies in the Americas.

Why did then the African slaves in the United States embrace Protestant Christianity and the enslaved African population at Saint-Domingue adopt Catholic Christianity?

The answer is simple. Historically, Protestant Christianity was the dominant religious expression in colonial America because the British empire was affiliated with Protestantism. By contrast, Catholic Christianity was the dominant faith of the French empire and thus influenced the religious environment in the French colonies of Saint-Domingue, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dominica, St. Lucia, Grenada, Tobago, etc.

During the colonial period, African slaves in the American society developed their own religious system and distinctive expression of Protestant Christianity, best articulated in the nature and structure of The Black Church, and the continuous practice of African traditional religion in their midst. The first Black Protestant denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, founded in 1816 by Richard Allen, bears considerable imprint of West African traditional religion and culture. Also, other Black Protestant denominations such as the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion) Church, founded in 1821, and the Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church, founded in 1870, have been also largely influenced by West African religious culture and tradition. It should be noted that Bishop Allen sent Black missionary delegates to Haiti, and in fact, the first Protestant church in Haiti was founded by African American missionaries.

Further, we can trace the origin of Black Catholicism to the French colonies in the United States, such as the state of Louisiana. (As a side note: It should be noted that French colonies [“New France”/ “Nouvelle-France”) in North America began in the early seventeenth century. One should remember that the Africans were already Catholic converts before the mass immigration to the United States. French settlers founded what is known today as Quebec in 1608. By 1682, the second-half of the seventeenth century, the French Empire expanded all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico and the Eastern region of Canada.)

In the same line of thought, African slaves at Saint-Domingue-Haiti also developed their own distinctive religious system expressed through Haitian Vodou and Haitian Catholicism. It should be noted that there were four religious systems that developed side-by-side in colonial Haiti and underwent New world innovation and creativity: the Dahomean religion best expressed through Vodou, Roman Catholicism, Islam, and eventually Protestant Christianity as early as (officially) in 1816—that is, only 12 years after the birth of the nation of Haiti. Historically speaking, some of these religious traditions have not enjoyed/ do not have enjoy the same religious freedom and rights in the Haitian society. For example, in contemporary Haitian society, Protestant Christianity is leading the way among those committed to religion.

In closing, I should also point out that Protestantism Christianity did not begin in Haiti in 1816. Protestantism already existed during the colonial period in Saint-Domingue. Few scholars of religion explored the adventurous life of the French naval officer François Levasseur, a Huguenot. The Huguenots, a dominant religious minority, were expelled from the overwhelming Catholic France. They were French Protestants in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and committed faithfully to the teaching and theology of the French Protestant Reformer and theologian Jean Calvin. On October 16, 1865, King Louis XIV or the “Sun King” (“Le Roi Soleil”) revoked the Edict of Nantes and characterized the Protestantism of the Huguenots as a heretical faith. The Huguenots were given the choice to renounce Protestantism and join the Catholic Church. They suffered great religious persecution even to the point of death in France.

Levasseur’s tremendous work marked the beginning of French colonization in Saint-Domingue. It is observed that Levasseur solicited support from fifty fellow Protestant Christians to drive out English settlers and explorers from the island of Tortuga, Haiti. Some would have argued that that he was the first governor of Saint-Domingue, and in 1640, he established his own government there. Interestingly, on November 2, 1641, governor Levasseur signed a treaty with Chevalier Philippe de Longvilliers de Poincy, the general who represented the King of France in the Caribbean islands, stated “Les religions catholique et protestante seraient sur le pied d’égalité” (“The Catholic and Protestant religions would be on equal footing”). The referenced article somewhat exceeded the provisions of the Edict of Nantes. However, Levasseur did not honor the terms of the treaty. Some have said that he was a violent and authoritarian leader. As governor of Saint-Domingue, he prevented Catholic practitioners to exercise their own religious freedom and rights. Some have noted that he even expelled out of the island his own Protestant minister. He was murdered in 1652, and it is believed that two of his closest friends were responsible for it.

**I am indebted to my friend’s clarity, the well-regarded Haitian sociologist of religion Lewis A. Clorméus on the final paragraph on Levasseur. Lewis published a recent essay on the subject matter.

“Aging Gracefully like Du Bois and Price-Mars”

“Aging gracefully like Du Bois and Price-Mars”

When I grow up, I want to be like Jean Price-Mars and W. E. B. Du Bois. In 1956, Price-Mars was 80 years old and had travelled all the way to Paris to attend an international conference organized by the Society of African Culture. In 1959, the “Uncle” was still energetic, at least intellectually, and he participated again in another international conference that took place in Rome, and he attended the Second Congress of Black Writers and Artists organized by Présence Africaine. Believe me, folks: he presented academic papers at both conferences.

Here’s another breaking news, Good People:

Finally, in 1966, three years before his death, the ninety-three-yr. old (90 years old I repeat!!!) prominent Haitian Pan-Africanist intellectual and the Dean of Black culture in the world—as many have called him—attended The World Festival of Black Arts, marking his first visit to Dakar, Senegal.

Doesn’t’ Jean Price-Mars remind you of the intellectually astute W.E.B. Du Bois in his late 80s and even early 90s was still traveling, writing, researching, and delivering conference papers. Did you know that Du Bois was 90 years old when he visited Ghana and initiated the landmark book project, that is, the creation of a new encyclopedia about the people of the African diaspora, commonly called “Encyclopedia Africana.” In 1961, Du Bois travelled again to Ghana to begin his editorial duty on the Encyclopedia.

Jean Price-Mars was born on October 15, 1876, and died in his home in Pétionville, Haiti, on March 1, 1969. He was 93 years old. W. E. B. Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, MA, and died in Acra, Ghana, on August 27, 1963. He was 95 years old. Alright, Good People. Like Du Bois, I am going to die at 95 years old, and I still have a half-century to live before I go home to be with my Lord. Like Price-Mars, I want to die in my native land: Haiti 🙂

Happy Saturday!

How to live Now: On the Ethical and Dignified Life!

How to live Now: On the Ethical and Dignified Life!

The older I am getting (I am 45 now), the more I am realizing this world is really upside down and people are hurting and looking for a place of hope and a belonging community, and a reason to make sense of this constantly-changing world.

As an optimist, I am also finding out that people don’t really care about your academic pedigrees and achievements; rather, they want to know if you are a team player and consistent in your commitments, and if you care for them and have a heart to serve, mentor, and lead with empathy and understanding.

These are the qualities students are looking for in an instructor.

These are the coveted virtues that the people you are leading desire in a leader.

Thus, the greatest challenge is my personal responsibility to make this world more beautiful and harmonious where there’s despair and animosity, and to connect different human communities and unite people to each other where there is a long line of apparent difference and division.

The people in the world are hungry for something that is both transcendent and immanent, that is, a reference point for wisdom and a repository of human excellence and light.

“Let’s go Meet Him with Me”

“Let’s go Meet Him with Me”

These two friends began this conversation while they were eating breakfast in the cafeteria.

The 16 year-old girl student: I have heard in the Bible that Jesus died for sinners. I guess that I am a sinner.

Therefore, Jesus died for me.

The 15 year-old boy classmate: We are children, not sinners. What is a sinner, anyway?

The 16 year-old girl student: Hmmm… The best way to explain it is when you lie to your parents and cheat on a quiz or an exam. These are not cool things to do the Bible says.

The 15 year-old boy classmate: What if the Bible isn’t true and Jesus never lived or died?

The 16 year-old girl student: I am still a sinner and remain one. The other day I just lied to my parents about hanging out with Samantha and Sydney at the mall. We actually hid in my room. I closed the door. She didn’t even notice that.

You know something, Chase.

The 15 year-old boy classmate: What is it, Amber?

The 16 year-old girl student: I still need to be delivered from the bad things I’ve done. Plus, I want to change and be a good girl to all my friends. My mom does not like it when I don’t tell the truth. Dad is upset when I tell lies or when I am mean to my little brother and the dog.

The pastor also says that it’s not good to lie and die as a sinner. This word bothers me a lot. I also wonder if my dog also sins when he does not do what I tell him to do. Is he going to die too?

The 16 year-old boy classmate: My dog listens to me most of the time, but I have no idea if he could sin like we humans do. But dogs can be annoying sometimes. My puppy is a nice and good dog. I do not believe he can sin like we humans do. Do you know something? I’ve been thinking about this for a long time:

What if sin is a human invention? Do you understand this… like it’s not real. It’s a fake thing like the Superman and the Spiderman.

The 15 year-old girl student: Let me think for a minute about these things…

Can I share with you what’s on my mind now?

The 16 year-old boy classmate: I am listening, but you need to hurry. The bell is going to ring in five minutes.

Although the word sin has its origin in human languages, like English, the reality of sin in human relationships and societies, expressed through acts of human violence, suffering, war, hatred, lack of compassion, exploitation, abuse, poverty, etc, continues to haunt the world and negatively transforms life itself in the world. Does that make sense to you?

The 15 year-old girl student: It’s going to be less than a minute. I want you to listen to me carefully.

The 16 year-old boy classmate: Hmm…this is a complex saying. It is hard to understand. What’s your point, Amber?

The 15 year-old girl student: Hmm… the bell is going to ring in two minutes. Hurry up and finish eating your food. I don’t want us to be late to Ms. Myers’ class. You know she will tell our parents if we don’t get to class on time.

Come with me and let’s go put the left over food in the trash can. I can tell you what the pastor says about your question. Is that okay with you, Chase?

The 16 year-old boy classmate: I don’t care. You can tell me.

The 15 year-old girl student: First of all, the pastor says last Sunday that all people need freedom, and even kids like us need God and freedom.

Chase: You and I need deliverance too. He also tells us that all human relationships need restoration and peace.

I just can’t believe the pastor also says that all of us, including the church youths, also need redemption because kids can’t be good on their own. They need to befriend Jesus so he can teach them all good things .

The 16 year-old boy classmate: We live in a free country. We already have freedom and rights as youths. Can you talk to Jesus, Amber?

The 15 year-old girl student: You are asking too many questions. We’re going to be late to class.

To answer your question quickly: I do, but I don’t know if he hears me all the time. But I whisper to him sometimes, especially before I go to bed at night and before I dress to school in the morning

The 16 year-old boy classmate: That’s super cool, Amber! Have you ever seen Jesus?

The 15 year-old girl student: Why do you like to ask hard questions? I am not even good at answering your questions. You keep asking them anyway. This is my last response. We are going to get in trouble with the Language Arts teacher. She is going to be upset and call our parents.

Okay, Chase I guess I’ll answer the last one My youth pastor says on Wednesday night that every person can see Jesus in another person. He also says to my youth group that everybody is a mirror of God.

Let’s go, Chase! No more questions for the day! My head hurts.

The 16 year-old boy classmate: Will Jesus be my friend too just like we are best of friends?

The 15 year-old girl student: Maybe. Come and see! I will show you how.

“Rethinking The Problem of Theodicy in Haitian Vodou”

“Rethinking The Problem of Theodicy in Haitian Vodou”

In contemporary Vodou scholarship, the notion of theodicy and the opposing binary of good and bad remains unfortunately an unexplored terrain. Vodou scholars have either reject both concepts as if they only belong to the Abrahamic religions or Asian religious traditions such as Buddhism.

Some of my friends who are specialists in Vodou boldly assert that there is no concept of sin, and good and bad in Vodou. Some have argued that “sin” is a Christian concept. It is not Vodou nor does one find it in any African traditional religions. Even if sin is not a basic element in Vodou theological vocabulary and rhetorical grammar, atonement is part of Vodou praxis and liturgy. More often, atonement in Vodou deals with human trespasses, transgressions, shortcomings, the break-up of a vow with a law, for example. These various names we proposed here all pertain to one’s relationship with the Vodou Spirit. In a nutshell, one must atone for one’s sins and seek reconciliation with the Lwa.

Interestingly, if one carefully studies various Vodou songs such as praise songs, thanksgiving songs, agricultural songs, songs of alienation and exile (i.e. Lapriyè Ginen [The Ginen Prayer], and Le grand recueil sacré, ou, Répertoire des chansons du vodou Haïtien [The great sacred collection, or, Repertoire of Haitian Vodou songs] by Max Beauvoir; Vodou Songs in Haitian Creole and English by Benjamin Hebblethwaite ) or examine exegetically Haitian novels (i.e. Masters of the Dew by Jacques Roumain, General Sun, My Brother by Jacques Stephen Alexis) and Vodou poetry (i.e. Un Arc-en-ciel pour l’occident chrétien : Poème, mystère vaudou (Poésie) by René Depestre. Translated by Colin Dayan, as A Rainbow for the Christian West: The Poetry of René Depestre), the notion of human transgression as sin and the failure to maintain balance, as well as the problem of theodicy is inevitable and deliberate in the Vodou proper, as well as in Haitian Vodouist imagination through texts and visual/plastic arts. Vodou aesthetics through Vodou art and aesthetic performances such as the “mizik ginen” and “mizik rasin” all narrate a vision of good and bad in this Religious tradition, and the “ideal world” we long for and that which has departed from the Vodou practitioner. Vodou practitioners also shout “Ichabod”/” The glory has departed!

In fact, “theodicy” is one of the major issues in the acclaimed Haitian novel Masters of the Dew, which accounts for the environmental crisis, natural disasters, drought, human death, animal death, and the hostility that exists between the peasants in the village of Fonds Rouge, the geographical and cultural setting of the novel. The problem of “theodicy” is momentous, omnipresent, and toxic in the Fond Rouges community, and it causes strife and disturbs the peace and harmony in the Vodouist community there. As a result, the much Vodou-devoted parents of the protagonist Jean-Manuel Joseph had to call upon the Vodou Lwa to find a solution to the problem of not only “natural evil” in the village, but also the predicament of human-inflicted pain and suffering in their midst.

Furthermore, in the Haitian Vodouist tradition and cosmological order, the mere existence of a multiplicity of Lwa, is by design, and the fundamental function of the Lwa is, with the help of human (volitional) agents, to create harmony, equilibrium, balance, and equity in the world. The Vodou Lwa not only represent the various ideals of how the world should be and could be, they are in fact representations of how the world ought to be. The Lwa as messengers of the Creator-Bondye (The “Good God”) also infers that the present world does not represent the intended will of God/Bondye, and that human beings have created another world that contradicts “the Ideal World” that Bondye has willed. Hence, the creation of the Vodoun (Spirits) exists by divine necessity so that human beings in cooperation with the Messenger-Lwa could eventually achieve the intended plan of their Creator-Bondye, the good God. Arguably, the Vodoun are Bondye’s promising notes to Vodou adepts. They exist to help human beings/Vodouists deal with theodicy.

Correspondingly, in Vodou hermeneutics, the Vodou spirits also articulate and embody concurrently the various expressions and manifestations of the divine will, desire, and plan. As messengers of the divine will, the notion that the Vodou spirits help to create a relational cosmic order and improve the interplays between human beings in the world is indicative (1) the present world is not the way it should be, (2) the present creation is out of order, and (3) that human nature is out of balance and has been altered by the anti-Bondye human dispositions such as the evil choices and actions free volitional agents orchestrate in the world. In other word, we live in a world that is not harmonious, balanced, and equitable; hence, human beings need the lwa to put all things and the creation as whole to the intended will of Bondye.

Another way to think about the reason the lwa exist in Vodou is to improve the world by readjusting its order and human relationships and fellowship, and reestablishing human shalom and wholeness. Yet the underlying question we ought to explore and seek to understand is this: What is the ontology of the things that are out of place and harmony in the universe? How can we identity them? How should we classify them? Can we place them in different categories? Can we classify them as bad and evil things? Or what makes the world not so good, some human relationships evil, and some human choices anti-Bondye?

Whether one refuses to accept (or reject) the idea of bad and good does not (does) exist in Haitian Vodou or theodicy is (or is not) an element in Vodouist conception of the world/worldview, the Vodouist must face the existence of evil in the world. (Please don’t be quick to say theodicy and the opposing binary of good and bad are Western and Christian concepts; they’re not African!). The Vodouist like every religious and non-religious person in the world is trouble about the problem of human suffering, oppression, and pain, as well as the relationship between the good God (“Bondye”) and the presence of evil in our community, city, nation, and in the world. African traditional religions just like the African-derived religions in the African Diaspora have their roots in the ancient Egyptian religions and spirituality. Ancient Egyptian religions have shaped African/African diasporic religious liturgical practices, ethical systems, divination system, theological beliefs, and moral principles. Ancient Egyptian religions and spirituality have left their enduring mark on the Haitian Vodouist tradition. An important resource that sheds some light about those parallels and connections relating to theodicy and good and bad actions can be found in the famous Egyptian “The Book of Dead.”

Arguably, religion is a human invention, and at the core of every religion, there’s a form of spirituality and attempt to achieve piety. One of the functions of religion is to help humans cope with the care, burden, and anxieties of this world. The Vodou religion is no exception, and Vodouists are affected everyday by the troubles and worries of this world; yet they consult the lwa to find out why and to find a solution? That is theodicy; that is the conflict between the “ideal world” Bondye envisioned for human beings and the world that is.

Six years ago, I published a major article to address the problem of theodicy in Haitian Vodou through an exegetical reading of Jacques Roumain’s famous novel, Masters of the Dew. It was published in the academic journal Theology Today, which is associated with Princeton Theological Seminary/PUP: “The Rhetoric of Suffering, Hope, and Redemption in Masters of the Dew: A Rhetorical and Politico-Theological Analysis of Manuel as Peasant-messiah and Redeemer,” Theology Today (October 2013) 70: 323-350.

Allow me to say this in closing: Many Haitian peasants and some people (some of whom are family members and friends, and my late grandmother whom I so loved and cherished was an ardent Vodou-Catholic practitioner, as well as the great Vodou priestess [Mambo] in her community in Haiti) that I know who practice Vodou are quite aware of the problem of good and bad and correspondingly the predicament of theodicy in their religion and in their everyday experience; interestingly, the intellectual study of the Vodou religion is playing an utopian game with the real life and the real experience of Vodou practitioners. Like other religious traditions, Vodou has its own challenges: some of those challenges are ethical, moral, theological, and existential. The Vodou scholar must make these challenges as part of his or her intellectual adventure and curiosity about the religion. The basic human disposition to all religion is curiosity and the attempt to discover truth, the ideal, and gain understanding.