Call for Papers

Between Two Worlds: Jean Price-Mars, Haiti, and Africa

Edited by Drs. Celucien L. Joseph, Jean Eddy Saint Paul, and Glodel Mezillas

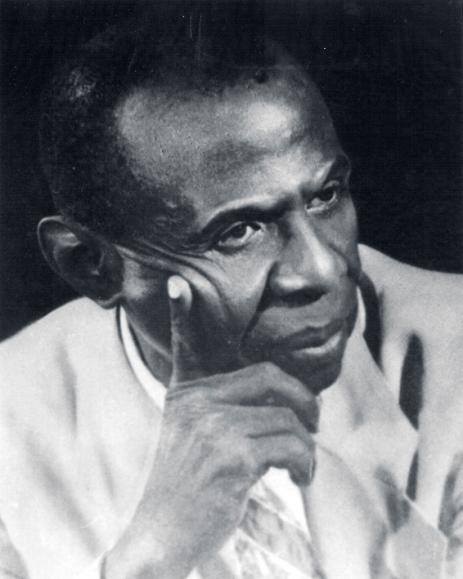

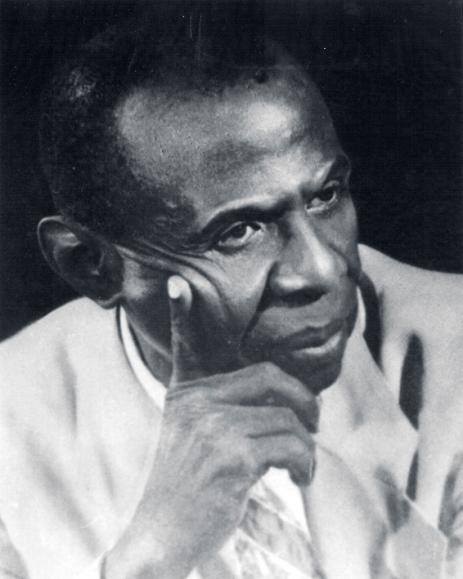

Jean Price-Mars (1876 – 1969), Haitian physician, ethnographer, diplomat, educator, historian, politician, was a towering intellectual in Haitian history and cultural studies, and a Pan Africanist who called to reevaluate the contributions of Africa in universal civilizations and to revalorize African retentions and cultural practices in the Black diaspora, especially on Haitian soil. Through his writings, Price-Mars, whom Leopold Sedar Senghor called “the Father of Negritude,” sought to establish connecting links between Africa and the Black Diaspora, and the shared history and struggle between people of African descent in the Diaspora.

For many scholars, Price-Mars is the father of Haitian ethnology and Dean of Haitian Studies in the twentieth-century, and arguably, the most influential Haitian thinker that has graced the “Black Republic” since the death of Joseph Auguste Anténor Firmin in 1911. In Haitian thought, Price-Mars has exercised an enduring intellectual and ideological influence on the young Haitian intellectuals and writers of the generation of the American Occupation in Haiti (1915-1934) and the post-Occupation culture from the 1930s to 1970s. He is especially known for launching a cultural nationalism and an anti-imperial movement against the brutal American military forces in Haiti.

The writings of Price-Mars were instrumental in challenging the Haitian intellectual of his leadership role in the Haitian society, and in promoting national consciousness and unity among Haitians of all social classes and against their American oppressor. Comparatively, his work was a catalyst in the process of shaping and reshaping Haitian cultural identity and reconsidering the viability of the Afro-Haitian faith of Vodou as religion among the so-called World religions. His thought anticipated what is known today as postcolonialism and decolonization.

Moreover, scholars have also identified Price-Mars as the Francophone counterpart of W.E.B. Du Bois for his activism, scholarly rigor, leadership efficiency, and his unremitting efforts to challenge Western racial history, ideology, and white supremacy in the modern world. Unapologetically, Price-Mars challenged the doctrine of white supremacy and the ideological construction of Western history by demonstrating the equality and dignity of the races and all people, and their achievements in the human historical narrative. As Du Bois, he was a transdisciplinary scholar, boundary-crosser, and cross-cultural theorist; in an unorthodox way, he had brought in conversation various disciplines including anthropology, ethnography, geography, sociology, history, religion, philosophy, race theory, and literature to study the human condition and the most pressing issues facing the nations and peoples of the world, as well as the possible implications they may bear upon us in the postcolonial moment.

Between Two Worlds: Jean Price-Mars, Haiti, and Africa is a special volume on Jean Price-Mars that reassesses the importance of his thought and legacy, and the implications of his ideas in the twenty-first century’s culture of political correctness, the continuing challenge of race and racism, and imperial hegemony in the modern world. Price-Mars’ thought is also significant for the renewed scholarly interests in Haiti and Haitian Studies in North America, and the meaning of contemporary Africa in the world today. This volume explores various dimensions in Price-Mars’ thought and his role as medical doctor, historian, anthropologist, cultural critic, public intellectual, politician, pan-Africanist, and humanist.

Hence, the goal of this book is fourfold: 1) The book will explore the contributions of Price-Mars to Haitian history, thought, culture, literature, politics, education, health, etc., 2) This volume will investigate the complex relationships between Haiti and the Dominican Republic in Price-Mars’ historical writings, 3) It studies Price-Mars’ engagement with Western history and the problem of the “racist narrative,” and 4) Finally, the book will highlight Price-Mars’ contributions to Postcolonialism, Africana Studies, and Pan-Africanism.

If you would like to contribute a book chapter to this important volume, along with your CV, please submit a 300 word abstract by Monday, February 29, 2016, to Dr. Celucien Joseph @ celucienjoseph@gmail.com, and Dr. Jean Eddy Saint Paul @ jsaintpaul@yahoo.fr

Successful applicants will be notified of acceptance in the first week of April, 2016. We are looking for original and unpublished essays for this book. Translations of Price-Mars’ works in the English language are also welcome. Potential topics to be addressed include (but are not limited to) the following:

I. Price-Mars as Historian

• Price-Mars as Historian

• Price-Mars’ engagement with Western history

• Price-Mars’ interpretation of Haitian history

• The function of Haitian heroes and heroines in Price-Mars historical writings

• The Origin (s) and History of Haiti and Dominican Republic in Price-Mars’ works

• Particularism and Universalism in Price-Mars’ historical writings

II. Price-Mars as Cultural Critic and Public Intellectual in Haitian Society

• Price-Mars as cultural theorist and literary critic

• The role of Price-Mars’ thought in the Haitian Renaissance in the first half of the twentieth-century

• Price-Mars and the Crisis of Haitian Intellectuals

• Price-Mars and the Crisis of Haitian bourgeoisie-elite

• Price-Mars, Vodou, and the Haitian culture

• The Haitian peasant in the writings of Price-Mars

• The Education of the Haitian masses in the writings of Price-Mars

• The problem of Race in Price-Mars’ writings

• Haitian Women in the thought of Price-Mars

• Price-Mars’ contributions as Medical doctor in Haitian society.

III. Price-Mars as Politician

• The Political career and goals of Jean Price-Mars

• Price-Mars, Haiti’s Ambassador to the nations

• Price-Mars and the American occupation and American imperialism

• The political philosophy and democratic ideas of Price-Mars

• Nationalism and Patriotism in Price-Mars’ thought

IV. Price-Mars as Pan-Africanist

• African history or the meaning of Africa in the writings of Price-Mars

• The Black Diaspora in the thought of Price-Mars

• Price-Mars’ Postcolonial Rhetoric and Linguistic Strategy

• The Vindication and Rehabilitation of the Black Race

• The Role and Contributions of Pre-colonial African civilizations to world civilizations

• Price-Marsian Negritude or Blackness

About the Editors

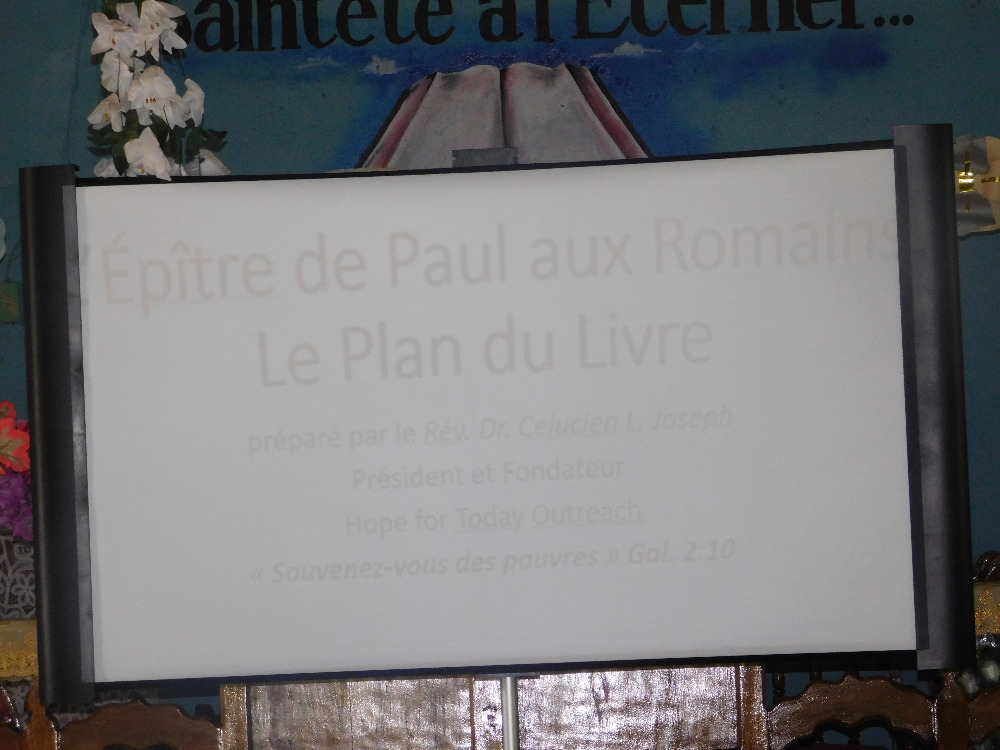

Dr. Celucien L. Joseph is currently an Assistant Professor of English at Indian River State College. He received his Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Texas at Dallas, where he studied Literary Studies and Intellectual History. Professor Joseph also holds an M.A. in French language and literature from the University of Louisville. In addition, he holds degrees in theological and religious studies. He serves in the editorial board and Chair of The Journal of Pan African Studies Regional Advisory Board; he also the curator of “Haiti: Then and Now.” He edited JPAS special issue on Wole Soyinka entitled “Rethinking Wole Soyinka: 80 Years of Protracted Engagement” (2015). Dr. Joseph is interested in the intersections of literature, history, race, religion, theology, and history of ideas.

Professor Joseph is the author of several books including Race, Religion, and the Haitian Revolution: Essays on Faith, Freedom, and Decolonization (2012), From Toussaint to Price-Mars: Rhetoric, Race, and Religion in Haitian Thought (2013), Haitian Modernity and Liberative Interruptions: Discourse on Race, Religion, and Freedom (2013), God Loves Haiti (2015). He has also contributed several encyclopedia entries and scholarly articles in various journals. His forthcoming book is entitled Thinking in Public: Faith, Secular Humanism, and Development in Jacques Roumain (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2016). He is the lead editor of a forthcoming two volume anthology entitled Vodou in Haitian Memory: The Idea and Representation of Vodou in Haitian Imagination (Collection 1), and Vodou in the Haitian Experience: A Black Atlantic Perspective (Collection 2)—to be published by Lexington Books in 2016. He is currently working on a volume on Jean-Bertrand Aristide, former President of Haiti and Catholic-Priest Liberation Theology entitled Aristide: A Theological and Political Introduction (under contract with Fortress Press).

Academic Bio of Jean Eddy Saint Paul, PhD, Sociologist,

Professor of Sociology and Politics

Universidad of Guanajuato (Guanajuato, Mexico).

Jean Eddy Saint Paul is a Haitian scholar and social scientist. He received his Ph.D. in Sociology from El Colegio de México (2008), an M.A. in Latin American Studies from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá (2002) and a B.A. in Social Work from the State University of Haiti. Dr. Saint Paul is a Professor of Politics and Sociology whose specializations include Religions, Citizenship, and Democracy, and Elites, Political Discourse and Ideologies. He currently works as a Professor for the Division of Law, Politics and Government at the Universidad of Guanajuato (Guanajuato, Mexico). He is also a regular Professor at the Inter-Institutional Doctorate (Ph.D.) Program in Law. Dr. Saint Paul is one of the founders of the Doctorate Program in Law, Politics and Government, and the Master Program in Political Analysis at the Universidad de Guanajuato. He usually teaches in the undergraduate and graduate programs and offers courses such as “Political Science”, “Sociological Theory”, “Politics and Religions”, “Political Theory” and “Qualitative Research Methods.” Before joining the University of Guanajuato, Dr. Saint Paul was a visiting professor of “Comparative Politics” and “Political Theory” at the Ph.D. Program in Political Science and Master Program in Sociology at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City.

Prof. Saint Paul’s work covers an unusually broad spectrum of topic including Historical Sociology of Politics, Politics and Religions (Secular State for Civil Liberties and Human Rights), Civil Society, Politics of Memory and Citizenship, Civil Society and Democratization from a Political & Sociological Perspective, Sociology of Violence, Patrimonialism, Neopatrimonialism, and Politics of the Belly. A Member of the National System of Scholars-CONACyT, level 1, Professor Jean Eddy Saint Paul was in 2013 a “Visiting Scholar” at the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Va. United States of America) and previously in 2011 was a “Visiting Fellow” at the Centre d’études et de recherches internationales (Centre for International Studies and Research (CERI), SciencesPo, CNRS, Paris.

Dr. Saint Paul conducts research on Latin America and the Caribbean, and has published his works in prestigious national and international press, like Karthala (Paris), Maison des sciences de l’homme (Paris) and El Colegio de México (Mexico). Among his recent publications on Haiti, it is important to mention: Chimè et Tontons Macoutes comme milices armées en Haïti. Essai sociologique, published in 2015 by the Cidihca press in Montreal (Québec), Canada; “La laïcité en Haïti. Approche sociologique des erreurs épistémologiques et théoriques dans les débats récents,” published in the international Peer Review Journal: Histoire, Monde et Cultures Religieuses (HMC), Thematic Number: Etat, Religions et Politique en Haïti (XVIII-XXI siècles), # 29, April 15, 2014, Paris: Karthala, pp. 83-100. ISBN: 9782811111540. Currently, he is working on two new books: Duvalierism, Rhetoric and Political Practices, and Civil Society and Politics of Memory in Haiti”.

Prof. Saint Paul is fluent in Haitian Creole, French, English and Spanish.

https://ugto.academia.edu/JeanEddySaintPaul.

Email address: jsaintpaul@yahoo.fr or jsaint@colmex.mx

Professional link: https://ugto.academia.edu/JeanEddy

His new book: Chimè et Tontons Macoutes comme milices armées en Haïti. Essai Sociologique. Montreal, Ca.: Cidihca, 2015.

http://lenouvelliste.com/lenouvelliste/article/151043/Chime-et-tontons-macoutes-la-logique-de-continuite

http://lenouvelliste.com/lenouvelliste/article/151043/Chime-et-tontons-macoutes-la-logique-de-continuite

Skype: Jean Eddy Saint Paul (Charlottesville)

Bio for Glodel Mezillas, PhD

Glodel Mezillas is a political scientist, theorist, philosopher, and a scholar of Caribbean and Latin American Studies. He received his PhD in Latin American Studies from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM), a Master’s degree in International Studies from Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2001-2002. He also studied at the Ecole Normale Supérieure (ENS) of the Université d’Etat d’Haïti, UEH), from which he received a Bachelor’s degree in Modern Letters, and at the Université Toussaint Louverture a B.A. in Political Sciences He has also done special studies in Diplomacy and International Politics at Escuela Diplomática de Madrid, and in International Public Administration (ONU) at the École Nationale d’Administration de Paris, Institut des Relations Internationales du Cameroun (IRIC),and at the Institut des Nations Unies de la Recherche et la Formation (UNITAR), he specialized in the field of United Nations System.

Dr. Mezillas has served as Professor of Genealogy of Postcolonialism at Instituto de Estudios Críticos, of International Relations and the Caribbean Studies at the Institut d’Études et Recherches Africaines (IERAH) de l’Université d’État d’Haiti, of International Relations at Université Polyvalente (Haiti), and Professor of Political Sciences and Epistemology of Social Sciences at the Université Toussaint Louverture. His teaching and scholarly research interests include Black Diaspora, Cultural, Political Theory and Epistemology of Social Sciences in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Dr. Mezillas is a prolific writer and has published in three languages English, Spanish, and French. His books including Que signifie philosopher en Haïti? Un nouveau concept du Vodou (L’Harmattan, 2015), El trauma colonial, entre la memoria y el discurso. Pensar (desde) el Caribe (EDUCAVISION, 2015), Qu’est-ce qu’une crise. Eléments d’une théorie critique (L’Harmattan, 2014), Civilisation et discours d’altérité. Enquête sur l’Islam, l’Occident et le Vodou (EDUCAVISION, 2014), Généalogie de la théorie sociale en Amérique Latine (Editions de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti, 2013), and Haití más allá del espejo (Editorial Praxis, 2011).

E-mail address: glodelmezilas@hotmail.com

Sincerely,

Celucien L. Joseph, PhD

Assistant Professor of English

Indian River State College

Curator of “Haiti: Then and Now”

http://www.haitithenandnowhtn.com/

Jean Eddy Saint Paul, PhD

Professor of Sociology and Politics

Universidad of Guanajuato (Guanajuato, Mexico)

Email address: jsaintpaul@yahoo.fr or jsaint@colmex.mx

Professional link: https://ugto.academia.edu/JeanEddy

Glodel Mezillas, PhD

Counselor and Diplomat

Haitian Embassy in Spain