“Center for Faith, Reason, and Dialogue with Dr. Joseph”

“Diskou Vodouyizan an Ayiti”

“Center for Faith, Reason, and Dialogue with Dr. Joseph”

“Diskou Vodouyizan an Ayiti”

“Center for Faith, Reason, and Dialogue with Dr. Joseph”

“Apprenons à vivre ensemble: Dix thèses sur le dialogue interreligieux et la compréhension entre le Vodou et le Christianisme en Haïti”

“Center for Faith, Reason, and Dialogue with Dr. Joseph”

Here’s the second part of my conversation on Bishop Gregory Toussaint, Vodou, & the Christian discourse in Haiti.

“Pastè Gregory Toussaint, Vodou, ak Diskou Kristyanis lan (Dezyèm Pati)”

“Center for Faith, Reason, and Dialogue with Dr. Joseph”

Pastè Gregory Toussaint, Relijyon, ak Chanjman an Ayiti (Premye Pati)

Check out my new piece, published by Rezo Nodwes:

““Se Kongo nou ye/ Se nèg Nago nou ye”: A Call to Remember, Change, and a new Direction in Haiti from Zenglen”

Thanks to the @rezo_nodwes editor for sharing my essay with a wider audience!

“Se Kongo nou ye/ Se nèg Nago nou ye: A Call to Remember, Change, and a new Direction in Haiti from Zenglen”

Abstract

In his exegetical analysis of the popular song, “fidèl” (“faithful”) by the well-known Haitian band Zenglen, Haitian-American scholar and writer Dr. Celucien L. Joseph draws lessons from the lyrical song and its ideology to discuss the power of Haitian ancestral heritage and rethink about Haitian future, as well as to envision a new direction in society by emphasizing the role of art to conscientize the Haitian people and foster human flourishing and national progress.

Introduction

Since the fall of the Duvalier regime in the 1980s, the Haitian artist (poet, novelist, musician, comedian, painter) has been playing a crucial role in Haitian cultural history as the voice of reason and the national conscience of the Haitian people. The Haitian artist has also assumed the role of a protester against the existential political bankruptcy of the Haitian state, the progressive decline of Haitian culture, and the enduring cultural amnesia in society. He is also a cultural critic that assesses the current state of affairs of the country by engaging in the dynamics of the country’s past, present, and future. He construes himself as an ethical guide to the people, the agent of transformation, and a coach and mentor to the new generation. These various pointers and signifiers could be observed in the rhetorical lyrics of Haitian musical genres (or musical syles), including mizik rasin, rara, twoubadou, rabòday, etc, as well as in the rhetoric of resistance and liberation embedded in the lyrics of Boukman Eksperyans, Zenglen, RAM, Boukan Ginen, Simbi, Racine Figuier, Kalfou Lakay, Rasin Kanga, and a host of others.

The Haitian artist, who works within this tradition of protest and cultural enlightenment, does not sing the poetic praise of Haitian charlatan politicians nor does he take their side on matters of politics, economy, governance, NGOs, and Haiti’s diplomatic relations with the most powerful nations, and the so-called the International Community. Rather, he narrates a song of poetic justice that condemns their unethical political habits and practices, immoral human behaviors, and egocentric ideologies that are often detrimental to the politico-economic progress and human flourishing in Haiti. For the artist, charlatan Haitian politicians have not always been faithful to the Haitian culture and the ideals and promises of the Haitian Revolution. Incontestably, they have been a force of resistance to political change. Their historic failure lies in their inability to cast a new political vision and their unwillingness to build a strong network system that will prioritize the basic needs (economic, health, educational) and welfare of the Haitian people. Using his songs as an emancipative weapon to effect revolutionary change and awaken the Haitian people, the artist-poet takes sides with the marginalized masses and the peasant class or rural dwellers who are often viewed as the underdog of history and “les rejetés” /” the outcasts” of (Haitian) modernity.

Nou pa ka Bliye/ We must not forget

In the song below “Fidèl” (“Faithful”) by the famous Haitian band Zenglen, is an example of the role of the artist as prophet, preserver of culture, and a force against imperial culture and neo-colonial mindset. The song “fidèl” is probably the most cherished melody in the Band’s 1990 album, aptly called “An Nou Alèz”/” Let’s be happy”—an expression that encourages a positive and joyful attitude in life. Indeed, the beautiful lyrics in the album recommend the Haitian individual and the collective to embrace happiness, pursue national peace, and to find reasons within the Haitian culture and tradition to be content and live harmoniously as a community and people that share a common history and identity.

In this famous song, the artist makes an urgent call to the Haitian people to remain “faithful” (“fidèl”) to the Haitian culture and to never forget Haiti. The Kreyòl adjective “fidèl” is derivative of the French “fidèle,” meaning to remain constant, such as being faithful to a promise; faithful to one’s ideals; steadfast to the collective memory; remaining loyal to a tradition; and staying true to a cause. In sum, the urgent call to stay “fidèl” is also a summon to remain true to national convictions, the shared allegiance of the Haitian people, and the common beliefs and ideologies that bind them together as a nation. What are those characteristics and national markers?

In the song, the artist infers that to abandon Haiti and the ancestral roots is an act of betrayal and cowardness. Thus, he could make a clarion call to his people to embrace their cultural identity and “remember” their ancestral heritage:

“Ayisyen nou ye,

Se Kongo nou ye

Men se Kongo nou ye

Se konpa nou jwe

Nati Kongo nou ye, nou ye

Se konpa nou jwe

Se nèg Nago nou ye, nou ye, nou ye

Se konpa nou jwe”

[“We are Haitians

We are Congolese

But we are Congolese

We play Kompa

We are of Congolese descent, we are

We play Kompa

We are a Nago people, we are, we are

We play Kompa.”]

Evidently, in this song, the poet-artist binds together nationality (“asyisyen”), ancestral group identity (“kongo,” “nago”), racial identity (“nèg”/ “Black”/” African”) and cultural markers or signifiers (“konpa”). To put it bluntly, we are Haitians, whose ancestral heritage and identity are originated from the Congolese and Nago people—among the other ancestral links represented in Haiti. Historically, the “Kongo” are a Bantu-speaking people, whose links are cultural, religious, political, and linguistic. They are a large group that spreads out across Western, Central, and North Sub-Saharan Africa. The “Nago” is an ethnic identifier associated with the Yoruba language group. In other words, the Yoruba people are also called the Nago people who are connected in religion, language, culture, politics, and tradition. By consequence, the Haitian artist identifies two dominant ethnic groups of African descent that constituted the Haitian nation to emphasize the African memory and presence in Haiti, and correspondingly, the common history that binds the Haitian people—regardless of their class, social status, education, skin color. Following the logic of Jean Price-Mars and his robust cultural nationalism articulated in his epoch-making book Ainsi parla l’Once (So Spoke the Uncle), published in 1928, the poet-historian gives primacy to the African heritage in Haiti by undermining Haiti’s other complementary heritages: European and native-indigenous American.

Art as Vehicle of Change

Putting on his historian glasses, the poet-artist in “fidèl” argues that national change always often links to resistance in Haitian history. Yet the Zenglen artist sees music (“konpa”) as a medium to effect cultural and political transformation in the country, and to bring the Haitian people together. He affirms his role in society as to “sow joy in everyone’s heart”/” nou ka simen lajwa nan kè tout moun”/ and the function of “Zenglen” is to prepare the way, an alternative path toward cultural revolution and national progress. The artist also emphasizes four other human virtues or qualities that are necessary to build the new Haiti and the promising future for the Haitian people: modesty, tenderness, love, and community.

He signifies that both love and tenderness will be used as catalysts to help move the country forward toward the new direction that Zenglen, through its art, is envisioning. The collective “nou” (“we”) is an imperative “plural” that must organize and search collectively for the new path of integral liberation and holistic renewal in the nation. The poet-artist insists that both mutual love and community will bind the Haitian people to achieve their end-goals. Accordingly, for the Haitian people “to go together” (“pou n ale ansanm”) and “to find another path” (“nou pran yon lòt chimen”), we must never turn our heads against love and each other, and without this fundamental human quality, the Haitian people will not be able to find the new path, move forward in the new direction, and create a new generation.

Lòt bò fwontyè/The Way Forward

The artist-poet, a member of the Zenglen group, believes that his band is a new brand that shifts the direction (“n’ale lòt bò fwontyè”) of culture and Haitian music. Zenglen means a new direction and a new path toward enlightenment (“Zenglen pe fè chimen an”). To remain faithful (“nou vle rete fidèl”) to one’s culture, heritage, identity, and African roots, is not only necessary for change; it is imperative for resistance and the next phase of evolution of Haitian music. For him, art will play a vital role in fostering a new mentality among the new generation of Haitian youth and contributing to the collective success of the Haitian people. Yet in four poetic statements, he exhorts his people:

“Sa k’ pou pranm pou m bliye music peyi mwen

Sa k’a pran m pou m bliye rasin an mwen

Sa k’ pou pran m pou m bliye music peyi mwen

Sa k’a pran m pou m bliye culture pa mwen”

[“What would it take for me to forget the music of my country?

What would it take for me to forget my roots?

What would it take for me to forget the music of my country?

What would it take for me to forget my culture?”]

Absolutely nothing!

The phrases “pou m” (“for me”) and “mwen” (“my”) appear four times in the stanza, and each individual occurrence reasserts the argument of the poet-artist. Both the phrase and the word stand emblematically for the collective voice and commitment of the Haitian people to (1) to never forget their art; (2) to never forget Africa; (3) to never forget their homeland; and (4) to never forget their culture. This call to memory and remembrance is both applicable to Haitians in Haiti and those in the diaspora. For the artist-critic, the call to the Haitian people to remain steadfast to their heritage and art will pave the way to a new country; yet the virtues of love, tenderness, community/konbit, and modesty are central elements in the process of rebuilding the nation that we so love: our Ayi cheri. The Haitian future is dependent upon these collective obligations and shared responsibilities.

Here is the link to listen to the lyric:

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mA6r5zOlbYI&t=20s](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mA6r5zOlbYI&t=20s)

Happy First Day of July, Good People!

A Few Things to do in July:

***I have no idea how I am going to get all these things done in only 31 days and one month 😊

***I stole this gorgeous picture from a Facebook friend. It’s Haiti, Folks. My nostalgic moment continues😢

Christian Theology, Affirmative Action, and Reframing a different Human Future (Part 1)

In light of the recent reversal of Affirmative Action by the US Supreme Court, I have been thinking about the role of Christian theology to assist us to move forward post-racially as a nation and a people. As a Christian theologian, I must first confess that theology is fundamentally a human invention, and theological doctrines are the product of human imagination and coordination. By articulating this perspective, I am also affirming the epistemological limits of the discipline of theology itself, and the many ways it may not contribute fully to improve social relations, political arrangements, and human dynamics in society. Secondly, I am also attesting to the intellectual constraints of theology to break certain barriers in society, including economic, political, cultural, gender, educational, or ethnic. In other words, I do not believe theology or theological thinking is adequate or has all the resources to help us solve all the mysteries and complexities in contemporary societies—especially those in the polarized contemporary American society. However, I believe that we should investigate the theological resources that are available to us to assist us in imagining and conceptualizing the possibility of a post-racial society and in reframing a different human future?

By stating that theology has both epistemological and intellectual limits, I am simply pointing out that every theological system or tradition (Liberal theology, Liberation theology, Feminist theology, Openness theology, Constructive theology, Black theology, Reformed theology) is grounded in a specific cultural tradition and geography that shapes its language, contents, and ways of expression. If geography and culture support the numerous ways we think and live theologically in the world and in communion with others, our theological tradition also reflects our respective culture and geography; thus, the temptation to rise above our own theological tradition to engage transculturally and globally calls for both intellectual modesty and theological humility.

Most Christian theologians believe that there is a revelatory aspect to Christian theology. The idea that God has voluntarily revealed his nature and perfect attributes, both communicable and incommunicable, transcendent and immanent, in the sacred pages of Scripture testify to this position. The belief that the Scriptures also have a revelatory character of the Divine provides the resource to think theologically both about the Scripture and God himself. A third proposition most Christian theologians embrace is that the moral qualities of God point us to the moral life we should aim for in this world, and that divine perfections are adequate to help humans create government, the arrangements of society and culture, the institution of laws, and the distribution of justice and equity in society. Finally, most Christian theologians maintain that the way of Jesus is a model for human living and relations, and that in the character of Jesus humanity finds the best available resources to foster the deeply-formed life in a tragically-fractured world.

Yet we must bear in mind everything that I said above about the virtues and merits of Christian theology is a form of hermeneutical exercise, but it is a form of intellectual gymnastics that has some consensual value among theologians, universally and globally. The theological vision of the Bible includes certain emancipatory concepts and ideas promising us there’s another way to live together in this world and correspondingly, there’s another way to (re-)organize human societies. The revelatory nature of Biblical theology provides a good orientation to explore the possibility to live, think, act, and govern post-racially in our contemporary moments.

Given that we already affirmed the revelatory character of both Biblical theology and Theological anthropology, we have adequate resources available to point us to the right direction, that is, to think anew and reimagine creatively a present and future that are not based on racial identities and categories in modernity. If the revelation of God provides enlightenment to the dark world and if divine revelation is the antithesis to anything that defers human flourishing and life together, then Biblical theology is an empowering enterprise we can lean on to progress toward personal growth and the collective realization of God’s original intent for human societies and governments.

I would like to close the first part of this conversation with this question: Could Christian theology provide us with a different language to undo the race concept and get rid of racial categories in society that are often deployed to describe certain human relationships, demonize certain populations, grant privileges and advantages to certain groups, and delay the common good in society?

Last week, I had an opportunity to have a conversation with John Morehead, the host of Multifaith Matters, about interreligious dialogue between Vodou and Christianity. It was fun!

phttp://johnwmorehead.podbean.com/e/celucien-joseph-on-christianity-and-vodou-in-dialogue-in-haiti/

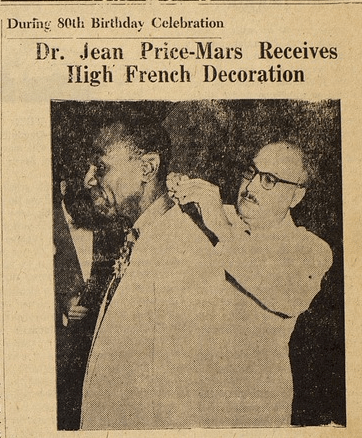

“Price-Mars: A Lesson on Perseverance and Commitment”

Here’s a lesson about commitment, perseverance, and dedication that I want to share with you from the life of Jean Price-Mars.

At 19 years old, Jean Price-Mars began his medical training at the National School of Medicine, Haiti’s only medical school at that time, located in the capital city of Port-au-Prince. In 1899, he received a government scholarship to finish his medical studies at “La Sorbonne”/University of Paris, in Paris, France. Due to financial difficulty, his studies were interrupted in 1901. Hence, he was forced to return to Haiti before getting his medical degree.

Twenty-two years later (I say 22 years later!), Price-Mars resumed his medical school in 1922 at the School of Medicine affiliated with Université d’État d’Haiti/the State University of Haiti. In 1923, he was awarded with his medical degree (M.D.) at 47 years old. Yes, he was 47 years old when he became a physician!

Immediately, he joined a medical team/clinic in Port-au-Prince to provide medical care to and cure the illnesses of the Haitian people. Because of his commitment to the Haitian peasants, the marginalized group in Haiti, he spent a lot of time riding his horse in the mountains and hills of Kenskoff to treat their diseases and make their life better. It was during his visits in Haiti’s countryside while spending time with the rural people that he began to do ethnological studies and attended more than 100 Vodou ceremonies. Jean Price-Mars would become the Father of Haitian ethnology and train thousands of students in the discipline.

His son, Louis Mars, following the footsteps of his famous father, also became a medical doctor. In fact, Dr. Louis Mars became the first Haitian psychiatrist. Like his father, he has written prolifically on the relationship between Vodou, psychiatry, and spirit possession. It should be noted that it was his father who inspired him to study psychiatric medicine, and he devoted his entire life caring for the Haitian people.