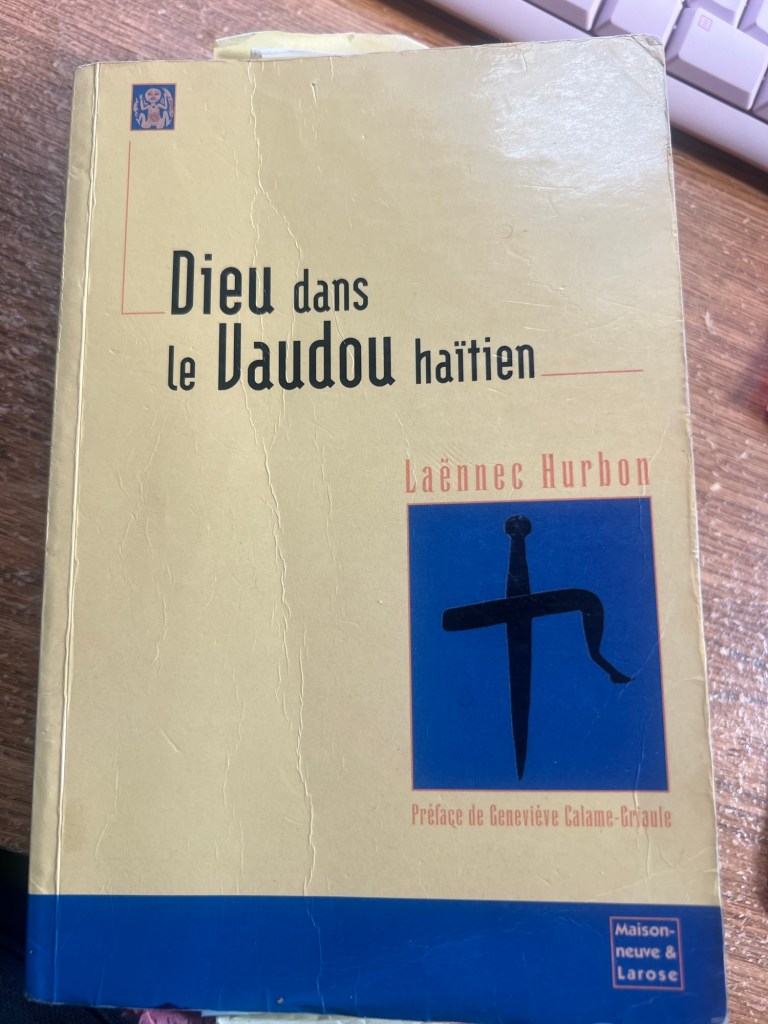

Laënnec Hurbon on the Role of Vodou in the Haitian Revolution

“Quelques malentendus sur le vodou et son rôle dans la

révolution haïtienne doivent être sinon levés, du moins éclaircis.

Toute une frange d’intellectuels appartenant au courant littéraire dit indigéniste des années 1940 a tendance à croire que le vodou a fait la révolution de 1791-1804, comme si les idéaux de la révolution française n’avaient eu aucune influence sur les esclaves. Certes, bien des mesures ont été très tôt prises pour empêcher que soient distribués à Saint-Domingue les journaux et pamphlets apportant des nouvelles de la révolution en France. Mais comment pouvait-on contrer cette influence puisque et les petits blancs et les libres de couleur revendiquaient sur la base même de la déclaration de 1789 ? D’un autre côté, l’insurrection n’a pas été une guerre religieuse contre les colons : elle a plutôt fourni un imaginaire qui a pu renforcer les capacités de lutte et le sentiment de solidarité entre insurgés. Il faut également signaler que de nombreux prêtres eurent à soutenir explicitement l’insurrection, dont le Père Cachetan, curé de Petite-Anse, et le père Philémon, curé du Limbé. D’autres encore ont agi en

négociateurs entre insurgés et colons. Il est révélateur que, capturé,Boukman, qui mena la révolte d’août, subit le même sort que le père Philémon : tous deux eurent au même moment la tête tranchée et exposée sur un pic sur la place d’armes du Cap. C’est dire que les influences ont été diverses. Avant tout, rappelons que la conscience des droits naturels chez les esclaves a été très forte car c’est elle qui les a mis en situation de révoltes régulières et poussés à la création d’une culture nouvelle, celle du vodou comme monde propre différencié de celui des maîtres. Par ailleurs, la franc-maçonnerie, présente notamment parmi les affranchis noirs et mulâtres, semble avoir eu une certaine influence dans le mouvement de révolte….

En revanche, même s’il est difficile d’établir en toute rigueur les faits (des divergences existent dans les récits sur les dates et parfois sur les lieux précis), force est de reconnaître que l’insurrection ne pouvait être menée en dehors de tout rapport au vodou…Le vodou a pu effectivement renforcer le courage des

insurgés en 1791 et des soldats dans leur combat pour l’indépendance en 1804. On peut dire que tandis que la révolution française s’enferme dans un universel abstrait des droits de l’homme (les Noirs et les femmes étant encore à cette époque maintenus exclus de ces droits, symptôme de l’ambiguïté des Lumières du dix-huitième siècle face à l’esclavage), on assiste à Saint-Domingue au travail de l’universel concret des droits de l’homme, c’est-à-dire à la mise en pratique effective de l’universalisme des droits de l’homme, en quoi apparaît l’originalité de la révolution haïtienne dans l’histoire universelle.”

–Laënnec Hurbon, “Le vodou et la révolution haïtienne” (2018)

English translation

” Some misunderstandings about Vodou and its role in the Haitian Revolution must, if not fully dispelled, at least be clarified. A whole segment of intellectuals belonging to the so-called indigéniste literary movement of the 1940s tends to believe that Vodou made the revolution of 1791–1804, as if the ideals of the French Revolution had had no influence on the enslaved population. Certainly, many measures were taken very early on to prevent newspapers and pamphlets bringing news of the revolution in France from being distributed in Saint-Domingue. But how could this influence have been countered, given that both the petits blancs and free people of color were making claims on the very basis of the Declaration of 1789?

On the other hand, the insurrection was not a religious war against the colonists; rather, Vodou provided an imaginative framework that could strengthen the capacity for struggle and the sense of solidarity among the insurgents. It should also be noted that many priests explicitly supported the insurrection, among them Father Cachetan, parish priest of Petite-Anse, and Father Philémon, parish priest of Limbé. Others acted as negotiators between insurgents and colonists. It is revealing that when captured, Boukman, who led the August revolt, suffered the same fate as Father Philémon: both had their heads severed at the same time and displayed on a pike in the main square of Cap-Haïtien. This shows that the influences at work were diverse.

Above all, it should be recalled that the enslaved had a very strong consciousness of natural rights, for it was this awareness that placed them in a situation of repeated revolts and pushed them toward the creation of a new culture—Vodou—as a distinct world, differentiated from that of the masters. Moreover, Freemasonry, present in particular among freed Blacks and mulattoes, seems to have had a certain influence on the movement of revolt.

By contrast, even if it is difficult to establish the facts with complete rigor (there are divergences in the accounts concerning dates and sometimes precise locations), it must be acknowledged that the insurrection could not have been carried out without some relationship to Vodou. Vodou did indeed strengthen the courage of the insurgents in 1791 and of the soldiers in their struggle for independence in 1804.

One may say that while the French Revolution locked itself into an abstract universalism of the rights of man (with Blacks and women still excluded from these rights at that time—a symptom of the ambiguity of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century with regard to slavery), in Saint-Domingue we witness the working out of a concrete universalism of the rights of man—that is, the effective practical realization of the universalism of human rights. In this lies the originality of the Haitian Revolution in universal history.”

–Laënnec Hurbon, “Le vodou et la révolution haïtienne” (2018)